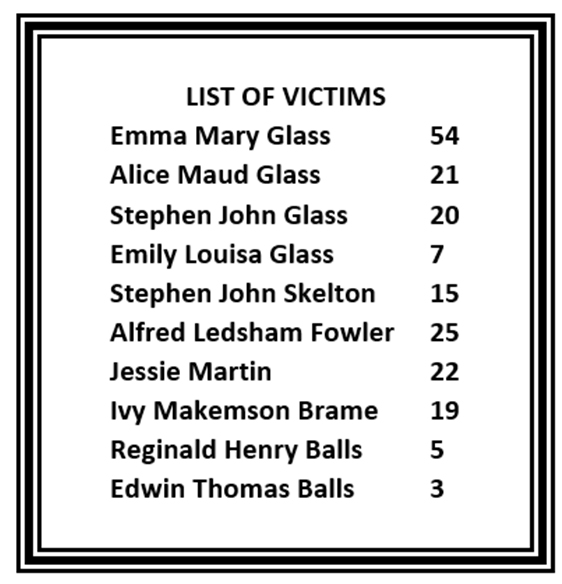

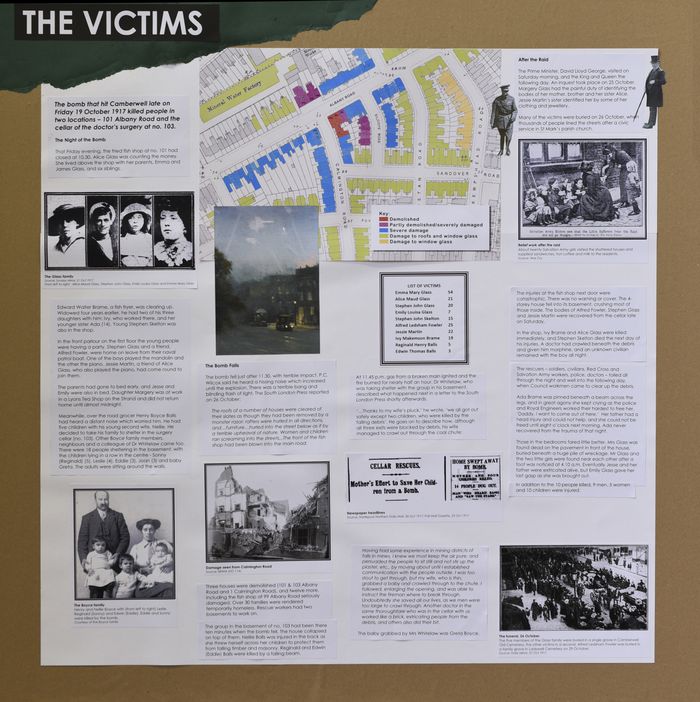

The bomb that hit Camberwell late on Friday 19 October 1917 killed people in two locations – 101 Albany Road and the cellar of the doctor’s surgery at number 103.

The Night of the Bomb

That Friday evening, the fried fish shop at no. 101 had closed at 10.30. Alice Glass was counting the money. She lived above the shop with her parents, Emma and James Glass, and six siblings.

Edward Walter Brame, a fish fryer, was clearing up. Widowed four years earlier, he had two of his three daughters with him: Ivy, who worked there, and her younger sister Ada (14). Young Stephen Skelton was also in the shop.

In the front parlour on the first floor the young people were having a party. Stephen Glass and a friend, Alfred Fowler, were home on leave from their naval patrol boat. One of the boys played the mandolin and the other the piano. Jessie Martin, a friend of Alice Glass, who also played the piano, had come round to join them.

The parents had gone to bed early, and Jesse and Emily were also in bed. Daughter Margery was at work in a Lyons Tea Shop on the Strand and did not return home until almost midnight.

Meanwhile, over the road grocer Henry Boyce Balls had heard a distant noise which worried him. He had five children with his young second wife, Nellie. He decided to take his family to shelter in the surgery cellar (no. 103). Other Boyce family members, neighbours and a colleague of Dr Whitelaw came too. There were 18 people sheltering in the basement, with the children lying in a row in the centre – Sonny (Reginald) (5), Leslie (4), Eddie (3), Greta (nearly 2) and baby Joan. The adults were sitting around the walls.

The Bomb Falls

The bomb fell just after 11.30, with terrible impact. P.C. Wilcox said he heard a hissing noise which increased until the explosion. There was a terrible bang and blinding flash of light. The South London Press reported on 26 October:

The roofs of a number of houses were cleared of their slates as though they had been removed by a monster razor; rafters were hurled in all directions, and…furniture…hurled into the street below as if by a terrible upheaval of nature. Women and children ran screaming into the streets...The front of the fish shop had been blown into the main road.

The group in the basement of no. 103 had been there ten minutes when the bomb fell. The house collapsed on top of them. Nellie Balls was injured in the back as she threw herself across her children to protect them from falling timber and masonry. Reginald and Edwin (Eddie) Balls were killed by a falling beam.

At 11.45 p.m. gas from a broken main ignited and the fire burned for nearly half an hour. Dr Whitelaw, who was taking shelter with the group in his basement, described what happened next in a letter to the South London Press shortly afterwards.

‘…Thanks to my wife’s pluck,’ he wrote, ‘we all got out safely except two children, who were killed by the falling debris’. He goes on to describe how, although all three exits were blocked by debris, his wife managed to crawl out through the coal chute:

Having had some experience in mining districts of falls in mines, I knew we must keep the air pure, and persuaded the people to sit still and not stir up the plaster, etc., by moving about until I established communication with the people outside. I was too stout to get through, but my wife, who is thin, grabbed a baby and crawled through to the chute. I followed, enlarging the opening, and was able to instruct the fireman where to break through. Undoubtedly she saved all our lives, as we men were too large to crawl through. Another doctor in the same thoroughfare who was in the cellar with us worked like a brick, extricating people from the debris, and others also did their bit.

The injuries at the fish shop next door were catastrophic. There was no warning or cover. The 4-storey house fell into its basement, crushing most of those inside. The bodies of Alfred Fowler, Stephen Glass and Jessie Martin were recovered from the cellar late on Saturday.

In the shop, Ivy Brame and Alice Glass were killed immediately, and Stephen Skelton died the next day of his injuries. A doctor had crawled beneath the debris and given him morphine, and an unknown civilian remained with the boy all night.

The rescuers – soldiers, civilians, Red Cross and Salvation Army workers, police, doctors – toiled all through the night and well into the following day, when Council workmen came to clear up the debris.

Ada Brame was pinned beneath a beam across the legs, and in great agony she kept crying as the police and Royal Engineers worked their hardest to free her, ‘Daddy, I want to come out of here.’ Her father had a head injury and could not help, and she could not be freed until eight o’clock next morning. Ada never recovered from the trauma of that night.

Those in the bedrooms fared little better. Mrs Glass was found dead on the pavement in front of the house, buried beneath a huge pile of wreckage. Mr Glass and the two little girls were found near each other after a foot was noticed at 4.10 a.m. Eventually Jesse and her father were extricated alive, but Emily Glass gave her last gasp as she was brought out.

In addition to the 10 people killed, 9 men, 5 women and 10 children were injured.

After the Raid

The Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, visited on Saturday morning, and the King and Queen the following day. An inquest took place on 25 October. Margery Glass had the painful duty of identifying the bodies of her mother, brother and her sister Alice. Jessie Martin’s sister identified her by some of her clothing and jewellery.

Many of the victims were buried on 26 October, when thousands of people lined the streets after a civic service in St Mark’s parish church.