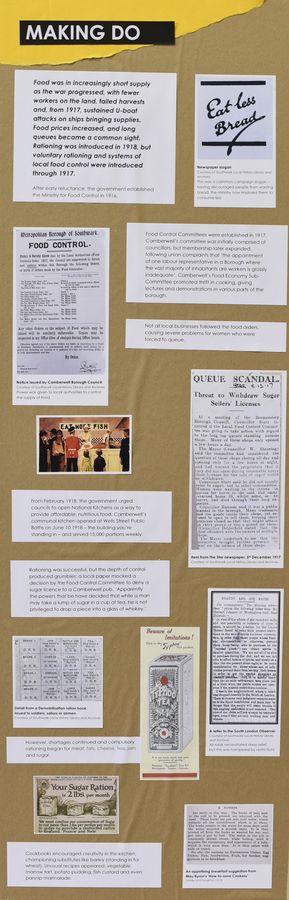

Food was in increasingly short supply as the war progressed, with fewer workers on the land, failed harvests and, from 1917, sustained U-boat attacks on ships bringing supplies. Food prices increased, and long queues became a common sight. Rationing was introduced in 1918, but voluntary rationing and systems of local food control were introduced through 1917.

After early reluctance, the government established the Ministry for Food Control in 1916.

Food Control Committees were established in 1917. Camberwell’s committee was initially comprised of councillors, but membership later expanded, following union complaints that ‘the appointment of one labour representative in a Borough where the vast majority of inhabitants are workers is grossly inadequate’. Camberwell’s Food Economy Sub-Committee promoted thrift in cooking, giving lectures and demonstrations in various parts of the borough.

Not all local businesses followed the food orders, causing severe problems for women who were forced to queue.

From February 1918, the government urged councils to open National Kitchens as a way to provide affordable, nutritious food. Camberwell’s communal kitchen opened at Wells Street Public Baths on June 10 1918 – the building you’re standing in – and served 15,000 portions weekly.

However, shortages continued and compulsory rationing began for meat, fats, cheese, tea, jam and sugar.

Rationing was successful, but the depth of control produced grumbles: a local paper mocked a decision by the Food Control Committee to deny a sugar licence to a Camberwell pub. ‘Apparently the powers that be have decided that while a man may take a lump of sugar in a cup of tea, he is not privileged to drop a piece into a glass of whiskey.’

Cookbooks encouraged creativity in the kitchen, championing substitutes like barley (standing in for wheat). Unusual recipes appeared: vegetable marrow tart, potato pudding, fish custard and even parsnip marmalade.