The Lime Kiln is now Grade II listed. It was built in 1816 by builders’ suppliers Edward R Burtt & Sons. Coal and limestone brought along the canal by Thames barge were burnt in the kiln for 3 days to produce quicklime, which was then reloaded onto barges for distribution. Quicklime was a key ingredient of mortar for houses and fertilizer for agriculture. As ‘limelight’ it was used to illuminate Victorian theatres. Burtt’s premises extended to Albany Road, and the kiln was in continuous use until 1925.

Producing quicklime by burning limestone is one of the oldest chemical reactions known to man. Limestone is a rock. It’s abundant, and quarried and mined widely. Quicklime (or just ‘lime’) has countless industrial uses, not least in making lime mortar. The Ancient Greeks and Romans used the same process.

Since Burtt’s was in full pelt at the height of the 19th century building boom in this area, it’s a safe guess that many local houses were held together thanks to quicklime from this very kiln. In theatres, before electricity, the bright incandescent glow of limelight (i.e. burning quicklime) was a forerunner to the modern spotlight. The Plantagenet kings even knew quicklime, as a weapon of naval war. It’s caustic, so could be projected at invading ships to blind the enemy.

So how did the kiln work? About 25 tonnes of limestone were brought in by barge. It was broken into small pieces, originally by hand. The 4 openings were loosely bricked up, and the kiln loaded with limestone, layered with coal, and lit from below. It burnt at over 1000˚C – that’s about the temperature of molten lava from a volcano.

Loaded 1 day, burnt for 3, allowed to cool for 2 days, then unloaded on the seventh day – a 1 week process. Lime kilns were once common, but few now survive in such beautiful condition. This one is Grade II listed. Most were on the coast or alongside canals, so the heavy load could arrive by boat. It wasn’t uncommon to have 7 kilns in close proximity, with loading/unloading gangs working a constant rotation. An isolated or occasional kiln – as this one eventually became – was known in the trade as a “lazy kiln”.

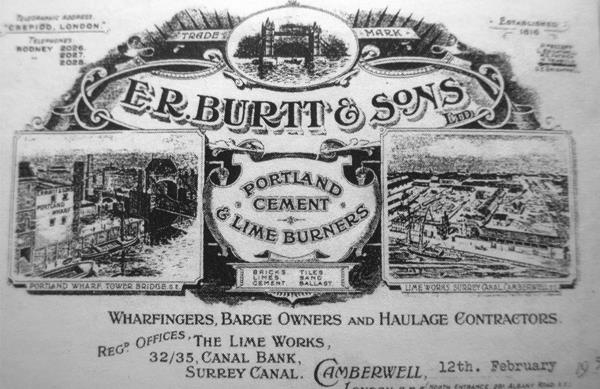

Burtt’s was a family firm, established 1816, trading not just in lime, but all sorts of building aggregates. Edward Robert Burtt himself was a Camberwell lad, born 1833. He retired successful, with 5 servants no less, around 1890, having passed the business to his son, Edward Burtt junior.

Edward junior fared less well. Development of the national railway network gradually made local small-scale kilns unprofitable, and many fell into disuse throughout the 19th century in favour of larger industrial plants. Burtt’s lived on though, trading also in Portland cement, and with a Wharf up at Tower Bridge, and even their own barges.

Edward junior would became a Lieutenant with the Army Service Corps, in World War I. Tragically, aboard the HMT Edward in 1915, he and a thousand men were drowned en route to Gallipoli, when the ship was torpedoed by a German submarine. He was just 46.

The business survived, and was still operating even in the 1960s. But the slow decline is writ large in the records – Burtt’s filed for liquidation in 1935, 1965, and finally again in 1975, having relocated. By then the canal had long been filled, and the old site’s increasing isolation in the now cleared park area was inescapable.

Ordnance survey maps of 1871 show Burtt’s neighboring a color works (dyes), just over Wells Way from two coal wharfs. Locals recalled the men leaving Burtts “with their hair all white and their eyebrows all white”. Presumably then sharing a pint with the blackened coal luggers & technicolour-splattered dyemen, at the pub on the bridge. The bath-house must have come as a very welcome arrival in 1903.

The kiln itself smouldered out for good in the fifties. But the story doesn’t end there. In 2002, it was lovingly restored by Groundwork Southwark. Local schools & community groups helped reveal its story in paving which you can still read at your feet as you circle the kiln.

So pleased to find this post – my great great great grandfather, William Goodman worked as a limeburner at E R Burtt’s – his address in the 1841 census is just Bankside. In the 1851 census William’s address is just shown as Lime Kilns and living next door at 2 Lime Kiln Cottages is 19 year old Edward Burtt with his father Charles, mother Louisa, 2 brothers, one sister and ‘only’ one general servant.

Thanks

I’ll be visiting Burgess Park this April (2015) from Australia

Hi Kate

Great to add your information to the site – many thanks for commenting. Hope you enjoy the trip.

Hi Kate, we found your info online. My mum is also a great great great grand daughter of William Goodman. We wondered if you ever found anymore info on William. We will be visiting there in 2024.

Having had a bull nose engineering brick in my garden for 40 years I now know where it originated!

awesome brick!