During wartime, governments have always tried to control the way people think and communicate with each other – and to stop them communicating with the enemy. Propaganda is useful, and censorship is seen as essential.

As with technology, WW1 saw a step change in the development and application of censorship.

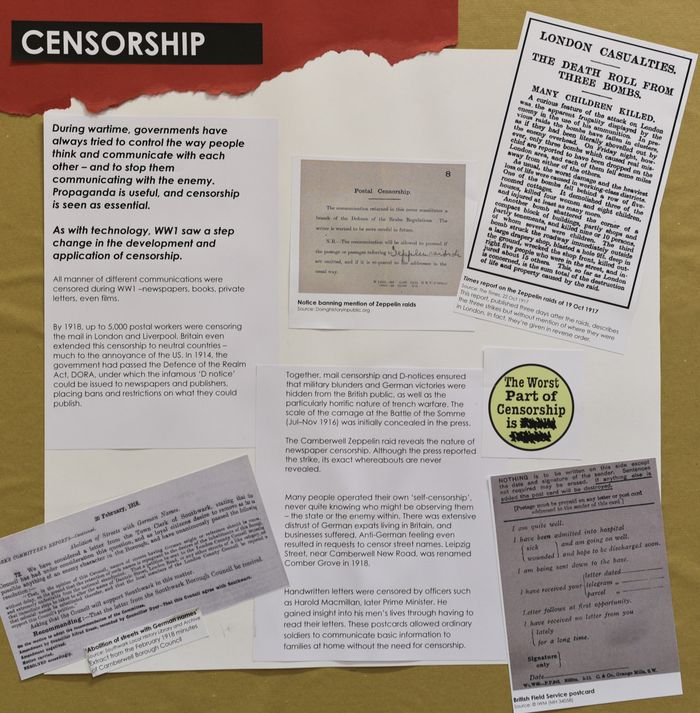

All manner of different communications were censored during WW1 –newspapers, books, private letters, even films.

By 1918, up to 5,000 postal workers were censoring the mail in London and Liverpool. Britain even extended this censorship to neutral countries – much to the annoyance of the US. In 1914, the government had passed the Defence of the Realm Act, DORA, under which the infamous ‘D notice’ could be issued to newspapers and publishers, placing bans and restrictions on what they could publish.

Together, mail censorship and D-notices ensured that military blunders and German victories were hidden from the British public, as well as the particularly horrific nature of trench warfare. The scale of the carnage at the Battle of the Somme (Jul–Nov 1916) was initially concealed in the press.

The Camberwell Zeppelin raid reveals the nature of newspaper censorship. Although the press reported the strike, its exact whereabouts are never revealed.

Many people operated their own ‘self-censorship’, never quite knowing who might be observing them – the state or the enemy within. There was extensive distrust of German expats living in Britain, and businesses suffered. Anti-German feeling even resulted in requests to censor street names. Leipzig Street, near Camberwell New Road, was renamed Comber Grove in 1918.

Handwritten letters were censored by officers such as Harold Macmillan, later to become Prime Minister. He gained insight into his men’s lives through having to read their letters. These postcards allowed ordinary soldiers to communicate basic information to families at home without the need for censorship.